The "right to be forgotten" appears to be unable to overcome the persistence of memory. According to a research paper due to be presented this week at the Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium in Darmstadt, Germany, search results removed from search indexes may still be discoverable.

The "right to be forgotten" follows from a 2014 ruling handed down by the European Court of Justice (ECJ), based on Europe's data protection laws. It provides support for those who wish to remove personal data from search engines under EU jurisdiction when that information is "inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant, or excessive in relation to those purposes and in the light of the time that has elapsed," as the ECJ put it.

The case originated in 2009 when Mario Costeja González, a Spanish lawyer, sought to have Google Spain remove a link to the online version of a 1998 article in a local newspaper about his need to sell property due to debt. The sale and debt had been resolved since the original article was published, so Costeja argued it was no longer relevant.

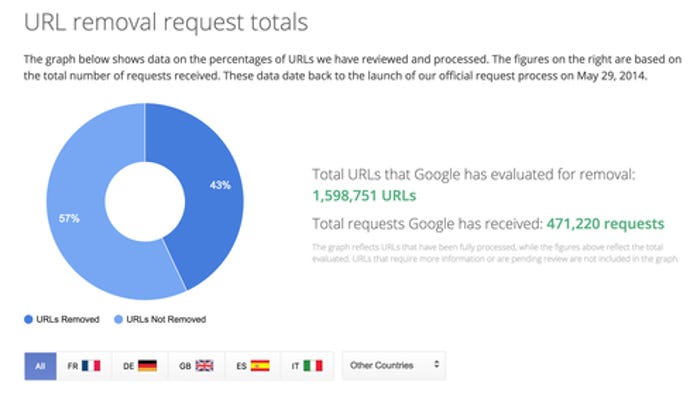

In response to the ECJ ruling, Google, Bing, and other search engines have implemented processes to request the removal of links from their respective search indexes, subject to approval. Delisting search results links in this manner does not remove the "irrelevant" web pages from the internet; rather delisting makes the source material more difficult to find through a search engine.

The "right to be forgotten" has been criticized as a form of censorship and a violation of free speech rights. Yet it also appears to be justified in some circumstances, such as to address revenge porn. Implementing "the right to be forgotten" in a way that's fair and resistant to abuse continues to challenge search engines.

The major flaw in the "right to be forgotten" is that it does not apply to Google.com in the US, where free speech presently enjoys strong legal protection, or in other countries outside of European jurisdiction. France's data protection authority wants Google to close that loophole.

While Google recently agreed to prevent searchers in the EU from discovering delisted material, such data remains accessible to anyone possessing the technical wherewithal to conceal or spoof his or her location. It's available too on websites that maintain records of delisted links.

Using a data set of 283 articles, researchers led by professor Keith Ross of NYU's Tandon School of Engineering, along with colleagues from NYU Shanghai and the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil, have found another flaw. A third party can potentially identify as many as 30% to 40% of delisted URLs and the name of the individual who requested the removal, the researchers claim.

Google does not show an article when the person who successfully requested its removal is named in the article, but it does show the article in response to search terms unrelated to that person's name. That discrepancy allowed researchers to construct an attack designed to identify delisted URLs without comparing search results for queries submitted to both Google.com and Google.co.uk.

[Read EU Data Protection Law May End the Unknowable Algorithm.]

As a demonstration of the attack, the researchers wrote a script that crawled and downloaded all the articles in El Mundo, a Spanish news website. Using that database of articles, the researchers ran a script that searched for a variety of topics commonly associated with removal requests, such as financial fraud and sexual abuse.

The script collected the names mentioned in the articles and then submitted those names to Google's site in Spain, google.es. When links to the known articles were not among the top 10 search results returned, the researchers were able to conclude that the named individual sought to have the article delisted.

The technique does not work in cases where the individual requester is not named in the article, but it turns out to be effective enough to call the feasibility of the "right to be forgotten" into question.

The researchers argue that Google should not notify webmasters when it delists links to their sites in order to avoid calling attention to delisted search results. They also see challenges for online forgetfulness.

They note that trying to suppress information may call more attention to it, causing the so-called Streisand effect. "Moreover, we do not see any effective defenses to these attacks, except for delisting the articles no matter what the query -- a defense many people would consider to be a strong form of censorship," they conclude.

When asked about the researchers' findings, Google declined to comment.

(Cover Image: Ivan Bliznetsov/iStockphoto)